The Size of the Cloth

May you, even in darkness, find your way home to light.

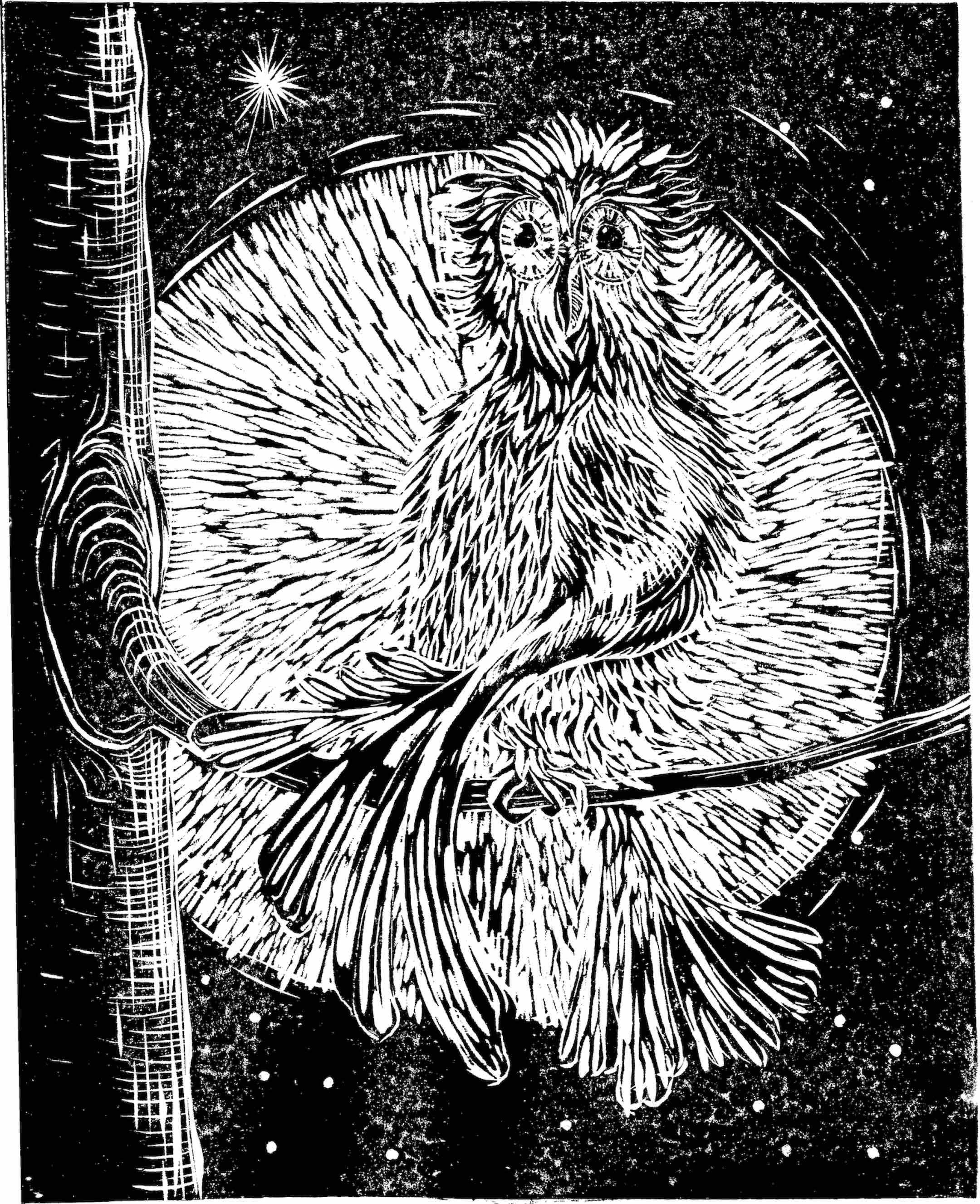

The Invitation, 2015, lino block print 8x10”

After finding Ursula K. Le Guin’s translation of the Tao te Ching, I purchased the e-book and began reading. She tells of how influential the Tao was in her life and how it informed much of her fantasy and science fiction writing. This turned me toward a novel of hers, Always Coming Home, that I’ve had since it came out in 1985. I was fifteen -- see how yellowed the pages are! I could never get into it, but I’ve hung onto it with the intention of finally reading it one day. It’s a complex, intricately woven story of a peaceful future society in what is now northern California. Le Guin uses art, poetry, prose, and more to really flesh out the story. So interesting, right?! But complex things used to turn me off. Perhaps I have a little more patience, perseverance, and time these days – enough to see it through.

In the novel’s introductory notes, she writes, “…no translation can give us the book that Lao Tze (who may not have existed) wrote. All we have is the Tao teh Ching that is here, now.” I keep the Feng/English translation of this book beside the recliner I’m often in and refer to it almost daily for inspiration. Having studied the Tao with one of my meditation teachers, I continue to find the ancient teachings reveal the mystery right here in everyday life. Here is chapter 15 from Le Guin’s translation:

Once upon a time

people who knew the Way

were subtle, spiritual, mysterious, penetrating,

unfathomable.Since they’re inexplicable

I can only say what they seem like:

cautious, oh yes, as if wading through a winter river.

Alert, as if afraid of the neighbors.

Polite and quiet, like houseguests.

Elusive, like melting ice.

Blank, like uncut wood.

Empty, like valleys.

Mysterious, oh yes, they were like troubled water.Who can by stillness, little by little

make what is troubled grow clear?

Who can by movement,

little by little make what is still grow quick?To follow the Way

is not to need fulfillment.

Unfulfilled, one may live on

needing no renewal.

Another set of fantasy books I’ve hung on to is C. S. Lewis’ Narnia series. They are relatively simple stories for children, but so rich in imagination and spiritual analogy. Aslan, (the wondrous golden lion obviously modelled on God) reads to me like the Tao. I used to reread that series regularly because it is uplifting and something in those stories fed my appetite for the mystery. On the theme of rereading books, has anyone else read and reread Rohinton Mistry’s novel, A Fine Balance? It’s a beautiful and terrifying story. The descriptions of life in the slums of India in the ’70s and of the trials of those in the untouchable caste are hellish. One character, Maneck, is set in relatively nourishing circumstances yet has a troubling possessive smallness that stains his view of the world. When he is engaged with friends in the city and sees the extent of their suffering it leaves him feeling helpless and hopeless. Even so, his tragic end made no sense to me the first two times I read the novel.

So I read it a third time a few years ago. My view on life had shifted a lot. For various reasons I had developed a more expansive view that included the suffering of others with whom I suddenly felt kinship. Naomi Shihab Nye writes in her poem, Kindness: “Before you know kindness as the deepest thing inside / You must know sorrow as the other deepest thing.” And not just that…

You must wake up with sorrow

You must speak to it till your voice catches the thread of all sorrows

And you see the size of the cloth

Then it is only kindness that makes sense anymore

Only kindness that ties your shoes and sends you out into the day to gaze at bread

Only kindness that rears its head from the crowd of the world to say

It is I you have been looking for

And then goes with you everywhere

Like a shadow or a friend.

Ishvar and Om, who were Maneck’s friends for a time, had been cracked open by indignity, pain, and loss. Om was bitter, but his older and wiser uncle, Ishvar, knew patience and kindness. He also had the long view of time’s oscillations. When their long struggle comes to even more desperate circumstances, they have each other and kindness “is the only thing that makes sense anymore.” They maintain contact with Dina, who had been a friend to all three of them. Despite her own desperate circumstances, she shares with them what she can and Om and Ishvar are grateful.

Toward the end of the novel, Maneck’s joyful anticipation at reuniting with his friends is crushed when he sees that they’ve been disfigured and beggared. He doesn’t see the kindness that is the sustenance of their lives and fear turns him away from them. In his own life, Maneck misses the opportunity to be kind -- to give up a chess set he is carrying, but refuses to use. It doesn’t occur to him to give it to a boy he meets and to whom the chess set would be a valued gift that he wouldn’t otherwise be able to own. All Maneck can see is suffering; all he feels is life’s betrayal. The chess set is a symbol of these hardships; they weigh heavy on him, but he cannot set them down. The indifferent, unfair, and disappointing nature of the intricate, infinite, chess game (Life) is what he clings to. By contrast, there is a quilt stitched together by seamstress Dina from scraps of fabric as all around her unfolds their stories of hellish suffering, periods of relief, and stolen joys. The quilt is like the Tao in it’s encompassing of Life’s choreography: of the very large to the very small, the visible and invisible, the real and the imagined, the horror and the joy. Representing this inconceivable tapestry woven in potent space and elastic time, the quilt ends up folded under the mangled body of Ishvar to soften his platform.

Ishvar is a steadfast literary thread woven through the tapestry of this novel. He sees and feels the hardship and tragedy, but doesn’t wallow in bitterness. He enjoys the small boons that come his way, but knows they won’t last. He is like one of those people of the Way of Tao described above. He has slept with sorrow, the least of which is his disfigurement; he knows the size of the cloth.

Perhaps I will read Mistry’s novel again in years to come and it will have more to teach me. Although I will have to buy a new copy as, in a perhaps overly thorough moment of decluttering, I seem to have given it away.

What book(s) are waiting for you to rediscover them?